|

| But what of Thrasher's fork? |

Our lead photo is from The Baffler's elegant summary: Weekly Bafflements: What a dogshit week.

Man, what a terrible week. Just an unrelenting deluge of morally bankrupt people parroting stupid opinions. Usually we round up a few good and funny things we read this week but honestly, everything is so fucking bad right now. So, here are some statues that are better than Confederate monuments.

The statue controversy? We visited this territory just this past May.

From Berlin to Budapest to New Orleans: "Historically, Confederate symbols have appeared at times of racial discord."

... Symbolism matters, but at the same time, if we're determined not to learn lessons from 152 years ago, symbolism just might be the least of our concerns.

Did these lessons somehow begin with the shelling of Fort Sumter? Of course not. As NAC's junior editor Jeff Gilenwater observed last week on social media:

I've seen several mentions now saying that comparing Confederate leadership to patently racist, pro-slavery, slave owning, slave raping, slave and any "other" murdering founding father types is a false equivalency. It's not. It's the latter who brought white supremacy to these shores in the first place and used it not just as justification for their own violent, self-serving actions but as the foundation upon which this country was built. If you're still clinging to some alternative mythology, perhaps you're not ready yet for the truths we have to accept. It's somewhat understandable given several hundred years of Eurocentric storytelling, but get ready anyway.

Mythology.

Hold on to that word; I'll get there in a moment. First, I point you to Daniel Suddeath's stand-alone commentary in the Glasgow Daily Times ("You can love the South without loving its biggest mistake.")

If anyone has to explain to you why supporting a group that believed it was OK to torture and murder people for personal gain isn't a good thing to do, you have bigger problems than worrying about the future of a statue. And that goes for supporters of the Confederacy and Nazis.

At Insider Louisville, Joe Dunman addresses the Castleman

Commentary: The Castleman statue has stood long enough

... Missing from our tour, and from Berlin in general, are any memorials to Hitler or any of his subordinates in the Nazi regime. No dignified bronze casts of Herman Goering or Josef Goebbels, no marble statues of Heinrich Himmler or Wilhelm Keitel on horseback. No murals of brave Wehrmacht soldiers marching off to invade France or Russia.

And yet, without any of these relics, the history of the Third Reich is alive and well in Berlin and across the rest of Germany. The country has not forgotten its past. In fact, it still works daily to reconcile with it. To atone. To make sure that through a very clear memory of what happened in the past, it will never make the same horrible mistakes again.

Don't worry -- I'm working my way around to the mythology. In the following video (circa 2009), historian James M. McPherson refutes the "states' rights" Confederate apologetic.

That's right, kids -- it really was slavery that ignited the American Civil War. Sorry about that faux "Lost Cause" verbiage. It's merely barroom banter after the fact.

In 2001, McPherson's argument in the lengthy book review linked below is a detailed, fact-based, well-nigh irrefutable case for slavery as first cause of the war. It's a long read, but it effectively rests the debate, and I've highlighted the "mythology" explanation.

Southern Comfort, by James M. McPherson (The New York Review of Books)

When Abraham Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address on March 4, 1865, at the end of four years of civil war, few people in either the North or the South would have dissented from his statement that slavery “was, somehow, the cause of the war.” At the war’s outset in 1861 Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, had justified secession as an act of self-defense against the incoming Lincoln administration, whose policy of excluding slavery from the territories would make “property in slaves so insecure as to be comparatively worthless,…thereby annihilating in effect property worth thousands of millions of dollars.”

The Confederate vice-president, Alexander H. Stephens, had said in a speech at Savannah on March 21, 1861, that slavery was “the immediate cause of the late rupture and the present revolution” of Southern independence. The United States, said Stephens, had been founded in 1776 on the false idea that all men are created equal. The Confederacy, by contrast,

is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and moral condition. This, our new Government, is the first, in the history of the world, based on this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.

Unlike Lincoln, Davis and Stephens survived the war to write their memoirs. By then, slavery was gone with the wind. To salvage as much honor and respectability as they could from their lost cause, they set to work to purge it of any association with the now dead and discredited institution of human bondage. In their postwar views, both Davis and Stephens hewed to the same line: Southern states had seceded not to protect slavery, but to vindicate state sovereignty. This theme became the virgin birth theory of secession: the Confederacy was conceived not by any worldly cause, but by divine principle.

The South, Davis insisted, fought solely for “the inalienable right of a people to change their government…to withdraw from a Union into which they had, as sovereign communities, voluntarily entered.” The “existence of African servitude,” he maintained, “was in no wise the cause of the conflict, but only an incident.” Stephens likewise declared in his convoluted style that “the War had its origin in opposing principles” not concerning slavery but rather concerning “the organic Structure of the Government…. It was a strife between the principles of Federation, on the one side, and Centralism, or Consolidation, on the other…. Slavery, so called, was but the question on which these antagonistic principles…were finally brought into…collision with each other on the field of battle.”

Davis and Stephens set the tone for the Lost Cause interpretation of the Civil War during the next century and more: slavery was merely an incident; the real origin of the war that killed more than 620,000 people was a difference of opinion about the Constitution. Thus the Civil War was not a war to preserve the nation and, ultimately, to abolish slavery, but instead a war of Northern aggression against Southern constitutional rights. The superb anthology of essays, The Myth of the Lost Cause, edited by Gary Gallagher and Alan Nolan, explores all aspects of this myth. The editors intend the word “myth” to be understood not as “falsehood” but in its anthropological meaning: the collective memory of a people about their past, which sustains a belief system shaping their view of the world in which they live ...

Finally, what to do with all those empty plinths? Public art, dad.

What To Do With Baltimore's Empty Confederate Statue Plinths? by Kriston Capps (CityLab)

Put them to work, Trafalgar Square style.

Baltimore suddenly has a surfeit of empty sculptural plinths. Overnight, Mayor Catherine Pugh and a fleet of trucks removed four Confederate monuments with a quickness not seen since the Colts skipped town. While other cities fret over what to do with Lost Cause memorials that are increasingly targets of ire and vandalism, Baltimore appears to have put the issue to rest.

With the statues gone, only opportunity remains. What can the city do with those empty (and now graffiti-covered) pedestal plinths? Baltimore could do worse than to take a page from London’s Trafalgar Square.

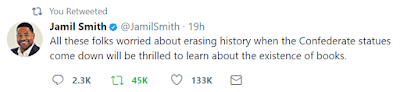

The last word goes not to me, but to Jamil Smith.

Happy demolition, sports fans.

No comments:

Post a Comment