The Economist reminds us that June 16 is Bloomsday.

Some will start their day with Leopold Bloom’s breakfast of “thick giblet soup, nutty gizzards, a stuffed roast heart [and] liverslices”. They might don a straw hat or a bowler, and stroll through Dublin, past Martello Tower and Sandymount Strand, ending at Kildare Street. The annual celebrations of “Ulysses” are not confined to James Joyce’s native Ireland: those in America, Australia, Canada, Italy or France can partake of dramatic readings, tea parties and plays. But many argue that this civilised annual knees-up is not true to the spirit of the notorious novel, first serialised in 1918 and banned for its frank portrayal of sexual desire and extra-marital affairs. Indeed, many tactfully ignore the reason Joyce set his masterpiece on June 16th 1904: it marked his first date with Nora Barnacle, his future wife, when she slid her hand into his trousers and “made [him] a man”. Best not to think about that over breakfast.

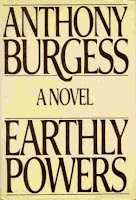

It's an apt segue for me, seeing as I've just completed reading Anthony Burgess's novel Earthly Powers.

History's nightmare -- the ongoing tale of human cruelty and oppression -- animates much of the work of both James Joyce and his most prolific disciple, Anthony Burgess.

The narrator in Earthly Powers is an English novelist named Kenneth Toomey, and it must suffice to say that Toomey has a pivotal experience in Dublin at the age of 14 -- on June 16, 1904, with one of Joyce's characters from Ulysses. For Toomey, this suggests a gaping hole in the plot of Joyce's novel, which of course is fiction. But is it?

Both Ulysses and Finnegan's Wake have defied my best efforts at reading. Many years ago I made it most of the way through the former, but did not finish, and as we used to say at the pub, finishing is crucial.

My question now: which version of Ulysses is my choice when the time comes to cross this book off the bucket list once and for all?

The Strange Case of the Missing Joyce Scholar, by Jack Hitt (New York Times)

Two decades ago, a renowned professor promised to produce a flawless version of one of the 20th century’s most celebrated novels: “Ulysses.” Then he disappeared.

Some 16 years ago, The Boston Globe published an article about a jobless man who haunted Marsh Plaza, at the center of Boston University. The picture showed a curious figure in a long overcoat, hunched beneath a black fedora near the central sculpture. He spent his days talking with pigeons to whom he had given names: Checkers and Wingtip and Speckles. The article could have been just another human-interest story about our society’s failing commitment to mental health, except that the man crouched in conversation with the birds was John Kidd, once celebrated as the greatest James Joyce scholar alive.

Kidd had been the director of the James Joyce Research Center, a suite of offices on the campus of Boston University dedicated to the study of “Ulysses,” arguably the greatest and definitely the most-obsessed-over novel of the 20th century. Armed with generous endowments and cutting-edge technology, he led a team dedicated to a single goal: producing a perfect edition of the text. I saved the Boston Globe story on my computer and would occasionally open it and just stare. Long ago, I contacted Kidd about working on an article together, because I was fascinated by one of his other projects — he had produced a digital edition, one that used embedded hyperlinks to make the novel’s vast thicket of references and allusions, patterns and connections all available to the reader at a click.

Joyce once said about “Ulysses” — and it’s practically a requirement of any article about the novel to use this quote — “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant.” And that has always been part of how the novel works. For most of the book, what you are reading are the fractured bits of memory and observation kicking around in the head of a single schlub named Leopold Bloom as he wanders about Dublin on a single day, June 16, 1904. It’s the sensation of putting these bits together and the pleasure, when it happens, of suddenly getting it — the joke, the story, the book — that compels you throughout.

This is why “Ulysses,” through most of the 20th century and into this one, still catches up all kinds of nonacademic readers who form clubs or stage readings on June 16. I remember wandering into an all-night read-a-thon on the Upper West Side, at Shakespeare & Co. on 81st Street, when I moved to New York in the 1980s. I arrived at the beginning, in the late afternoon, with good intentions, but staggered home and then returned the next day for the final chapter and suddenly realized that, read aloud, the 24 hours of the book’s action take 24 hours to read. The running time in your head is the same as the running time in the book. For a few minutes, I thought I was onto something brilliant, until another yawning fan in the bookstore mentioned a set of connections she had found and I realized, Oh, right, we’re all doing this ...