One of my goals for the bottle list at Pints&union is to have a hefty core of Belgian ales, and whenever possible, glassware to match.

This owes to several factors, among them the incredible and persistent vibrancy of Belgian ale brewing, as well as the patriotic need to spotlight these ales at a time when the multinational criminal organization calling itself AB InBev spends billions to persuade the easily duped that insipid Stella Artois golden lager represents Belgian beer at its finest.

Um, no.

Narrowing the focus, a particularly wonderful sub-culture within Belgian brewing is that occupied by the Trappists, or those ales brewed at Trappist monasteries. In recent years, this practice has spread outside the original six Belgium (and the seventh in the Netherlands) to Austria, Italy, the UK and even Massachusetts.

These thoughts are occasioned by a chance meeting with this article about Orval.

ORVAL: BORN OF A LEGEND, by Heather Vandenengel (All About Beer Magazine)

... Orval’s masterful complexity and drinkability have cemented it as a classic, particularly among brewing industry professionals like Allagash’s Rob Tod, Russian River’s Vinnie Cilurzo and New Belgium’s Kim Jordan, all of whom have cited Orval as a favorite beer.

“It is really the beacon of a particular style,” says Jordan, who praises its rocky, voluminous head, subtle Brettanomyces character and sturdiness of the malt combined with light peppery notes and a dry finish.

Like any enduring classic, Orval is also born of a legend. So the story goes: The widowed countess Matilda of Tuscany mistakenly dropped her wedding ring into a spring. Distraught, she prayed to God for its return and shortly thereafter a trout surfaced with the ring in its mouth. Matilda exclaimed, “Truly this place is a Val d’Or!” or “golden valley” and, overjoyed, she gave the land to the church, which built a monastery there, founded in 1070.

The brewery was established at the site of the Abbaye Notre Dame D’Orval in southern Belgium in 1930 and has produced just one packaged beer since then: Orval in its distinctive 11.2-ounce bottles with a trout, ring in mouth, on the label. (It also brews a lower-alcohol version of Orval, available on draft at the brewery and occasionally bottled.)

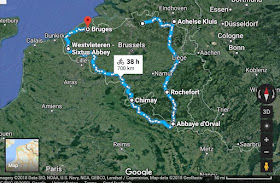

The lower-alcohol version of Orval is available at the A l'Ange Gardien cafe, a short walk from monastery's entrance, and I know this because in 2004, a half-dozen metropolitan Louisvillians rode our bicycles to all the Trappist monasteries in Belgium that brew beer -- stopping occasionally along the way to drink one or two of them.

Here's the Florenville-Orval-Florenville-Revin-Chimay segment, and yes, those are some challenging hills.

I've never written a truly comprehensive account of our personal Tour de Trappiste; however, it was mentioned in column I wrote for the defunct New Albany Tribune, written prior to the advent of the newer Trappist brewers outside Benelux.

Suffice to say, it was one amazing ride, alternately hellacious and holy, and we weren't once struck by lightning, righteous or otherwise. ABVs are another story.

Orval was an undisputed high point, owing both to its gorgeous physical location and the entirely unexpected tour of the brewing facility that we were afforded, which provided the opportunity to taste Orval at each stage of its creation.

Some day there'll be time to collate the photos, haul the banker's box out of the basement and give this ride the documentation it deserves. Until then, here is the lightly edited column from 2009.

---

True religion, Trappist-style.

Give me that old-time religion,

Give me that old-time religion,

Give me that old-time religion,

It's good enough for me.

The merits of old-time religion seldom are displayed to better and tastier effect than by the delicious ales brewed on the premises of six Trappist monasteries in Belgium and a seventh in the Netherlands. The beer world knows these holy places by the names of their beers: Achel, Chimay, Orval, Rochefort, Westmalle, Westvleteren and Koningshoeven.

There is an eighth member of the International Trappist Association (founded in 1997): Mariawald, in Germany, which to my knowledge is not a beer producer, although it is rumored to sell a proprietary liqueur. Since the Trappist appellation extends to all products emanating from member monasteries, perhaps Mariawald makes cheese or some other food suitable for accompaniment with beer.

There are many such pairings, as we learned in 2004, when our merry band of intrepid local beercyclists embarked on a quest for the grail at each of the six Belgian brewing monasteries. After tuning our bicycles in Amsterdam, we rode the train to Roosendal, peddled across the frontier and fought through mud and rain to Westmalle for lunch.

During the twelve days that followed, a veritable circumnavigation occurred. Second was Achel, followed by Rochefort and a dawning realization that the Ardennes indeed are to be considered mountains, not mere hills. Orval, then Chimay, and finally we broke away from French-speaking Hainaut province and arrived in West Flanders for Westvleteren and a meeting with a Belgian television film crew, which was assigned to chronicle strange things that foreign visitors do in Belgium.

It was our own Tour de Trappiste, and I’ll never forget it.

----

It sometimes surprises pious Americans that a religious order would undertake the production of alcoholic beverages. It shouldn’t. In days of yore, which in practical terms signifies the Dark Ages through Napoleon, European monasteries owned vast, self-sufficient agricultural estates. These testified to the pervasive power of the Roman Catholic Church, and from the time of the Reformation, events conspired to steadily erode the economic clout of these monastic entities.

From the start, monasteries in southern climes grew grapes and made wine. Further north, barley and other cereal grains were fermented into beer. In both cases, considerations of “sin” did not enter into this purely practical equation. Wine and beer preserved the value of perishable foodstuffs, provided a finished product that could be sold or bartered, and offered daily nourishment to the monks. So it goes today, albeit on a vastly reduced scale.

For certification as a Trappist brewery, the brewing operation must be located on the grounds of the monastery, although as in the case of Chimay, later stages of the process can be finished elsewhere. Monks must retain involvement and overall control of the brewing operation, but can hire secular brewers. Finally, a portion of the profits accrued from the brewing must go to specified charitable purposes.

The remaining brewing monasteries in Benelux have combined to develop a badge that signifies compliance with these requirements. Beyond denoting origin, neither the badges nor the word “Trappist” implies precise characteristics. All are top-fermented ales, with some dark and others pale. A few are hoppy, and others sweet. “Trappist" is an accredited appellation of origin -- nothing more, nothing less. The rest is up to the individual monastery brewing tradition, and results vary.

Arguably, Chimay Blue and Westmalle Tripel are the best known Trappist ales among casual beer lovers. The first is dark and belongs with red meat, while the second is pale and magical with seafood. Achel’s signature Kluis is relatively new, just like the revived brewery that brews it, and Westvleteren 12 remains reverential, if seldom seen outside Belgium.

Orval comes from a rural monastery with a physical setting that is the most stunning of all, with a jumble of newer buildings and older ruins nestled in a forested valley where time seems to stop. The utterly unique hop and yeast character of Orval is rewarding, but to me, the highest achievement of Belgian Trappist brewing remains Rochefort 10, which issues from the reclusive Abbaye Notre-Dame de St. Remy near the isolated Ardennes town of Rochefort.

My cherished Rochefort 10 weighs in at 11.3% abv (alcohol by volume), and safe, light lawnmower beer it isn’t, pouring creamy brownish-black, with mellow, deeply fruity esters and subtle hints of nuts. The flavor is pure silk, full-bodied, tasting perhaps of semi-sweet chocolate, with an alcohol note or two suggesting licorice liqueur. It is contemplative and refined, and should be sipped slowly for dessert.

In the traditional world of beer, imitation, flattery and profit are interwoven. Numerous breweries in Belgium, Netherlands and elsewhere release a cornucopia of “Abbey” ales, and these range from the inspired to the simplistic. Only ales marked with the approved seal can be called Trappist, but there is considerable overlap between these and the many Abbey imitations. The only way to chart the similarities and differences is to drink as many different varieties of both as possible, and that’s why it’s fun being a professional.

The monks may devote their entire lives exploring the relationship between man and God, and while doing so, they follow the time-honored Rule of St. Benedict and the guidelines of the Cistercians of the Strict Observance. We can be thankful that in seven locations, the same brothers augment their cosmic search with the science of fermentation, keeping venerable brewing traditions alive.

No comments:

Post a Comment