Joining in prayer: In defense of the 'Bune's Morris, Rep. Mike Sodrel appeals for us to "put up with" him.

(Note: Rep. Sodrel's column has yet to be archived on-line).

(Note: Rep. Sodrel's column has yet to be archived on-line).In some mysterious way, it is flattering to have provided a suitable pretext for a campaign speech, as I have been strangely transformed with the publication in the Tribune last week of “America started and is a Christian nation,” a guest column by the noted historian, 9th District Congressman Mike Sodrel.

Plainly, had I not the audacity to dispute the paucity of facts and dubious reasoning offered by the Tribune’s Chris Morris in a similar column espousing the precisely same position, it is highly doubtful that Rep. Sodrel would have taken valuable time away from grappling with the many serious problems facing America and the world in 2006 to trot out the familiar, tired clichés about the Founding Fathers and their theocratic intentions with respect to religion, freedom and the American way of life.

That Rep. Sodrel has done so – that he must opportunistically respond in such a manner to an academic exchange of opinion (well, half of one, at least) in a small-town newspaper – tells us more about the exigencies of Red State politics and the need to bolster the fundamentalist voting bloc in key part of his district in the run-up to an election year than it does about the congressman’s selective reading of history in the context of his acceptance of Jesus Christ as personal campaign manager.

Not that I doubt his sincerity when it comes to personal religious convictions. However, the persuasiveness of his argument is another story entirely.

Whereas Chris “Ed Anger” Morris offers precious few facts of any sort in his “Religion is who we are” column, Rep. Sodrel throws out bright and bouncy clusters of them during the course of a rambling essay running twice the length of my response to Chris’s original rant, but unfortunately, few of the genuine facts are connected to each other, and just as many are anecdotal and utterly irrelevant to the case Rep. Sodrel earnestly seeks to make.

For instance, following a passage in which he cites Article 6 of the U.S. Constitution (“No religious test shall ever be required … ) as evidence of the Founding Fathers’ commitment to allowing “citizens of any faith, or of no faith” to participate in government, Rep. Sodrel proceeds immediately to a denunciation of an unidentified “minority” effort to have “In God We Trust” removed from all American currency.

Rep. Sodrel obviously is implying that these words imprinted on our money are directly related to the Founding Fathers and their Christian wisdom. What he doesn’t tell you is that not until the end of the American Civil War did the phrase “In God We Trust” began to be seen each and every time that a Druid handed a prostitute her fee in coins or greenbacks.

(As a contrarian and an atheist, seeing such a blatant religious advertisement on my cash is only mildly annoying, because when it comes time for me to spend it, my concerns are less with the unknowable deity being blurbed than with my loot’s continued viability as “legal tender for all debts, public or private.”)

(God may or may not be many things, but He is not the Fed.)

Looking around the vicinity of his office in Washington D.C., Rep. Sodrel notices visible signs of our “Christian heritage” everywhere, and to him, these constitute unmistakable evidence that, as John Adams once wrote, “we are a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to govern any other.”

I’d argue that these outward manifestations of generic Christianity tell us a great deal about theories of exterior design, style, ornamentation and the human instinct for public decoration, and that the friezes on the Parthenon provided similar “evidence” of whole panoplies of Gods that have since passed from the scene.

It remains that most of the people you hear advancing the “America as Christian nation” argument unintentionally confuse two distinct considerations, for there is a crucial distinction between believing in God in the most general sense (something that isn’t disturbing), and espousing a specific system of beliefs using God as justification (Christianity, Islam, Judaism and all the shadings of each).

Ask a man on the street whether he believes in the existence of God, and you’ll establish whether or not he’s a theist, strictly speaking. However, theism in and of itself does not provide a clue as to the belief system that follows from his basic recognition of a “higher” power.

He believes in God … but which one?

This is why arguments like Rep. Sodrel’s are ultimately unconvincing to me, because while it is true that most of the Founding Fathers were Christian, and also true that many of them uttered words to this effect at one time or another, the specifics of their respective personal theologies obviously differed as widely as their practical daily political beliefs. We must ask, then, that if they meant for their new enterprise to be “Christian,” exactly what did they have in mind?

Rep. Sodrel duly attempts to answer this question by placing morals and ethics in a necessarily religious (read: Christian) context, but this needn’t be the case. A secular, reality-based ethical system has just as much viability as one dependent on supernatural sanction, although it has the drawback of providing employment for fewer men and women of the cloth.

Finally, even if we assume that the varying Christian beliefs of the Founding Fathers can be woven collectively into a consistent pattern, would this amalgam be of any relevance to the world as it is today?

As Sam Harris points out in his masterful “The End of Faith”:

"Imagine that we could revive a well-educated Christian of the fourteenth century. The man would prove to be a total ignoramus, except on matters of faith. His beliefs about astronomy, geography and medicine would embarrass even a child, but he would know more or less everything there is to know about God. Though he would be considered a fool to think that the earth is the center of the cosmos, or that trepanning (boring holes in the human skull) constitutes a wise medical intervention, his religious ideas would still be beyond reproach. There are two explanations for this: either we perfected our religious understanding of the world a millennium ago – while our knowledge on all other fronts was still hopelessly inchoate – or religion, being the mere maintenance of dogma, is one area of discourse that does not admit of progress."

The same can be said of the 18th-century resident of the United States.

Isn’t it strange that the vast majority of Americans eternally clamoring for a return to the values of the Founding Fathers conveniently ignore other accepted teachings of the era, some of which we now understand as vile and repugnant … even, heaven forbid, evil in the ethical sense?

Where to begin with the recitation of human practices and conditions not merely tolerated by the churches of the past, but sanctioned and encouraged?

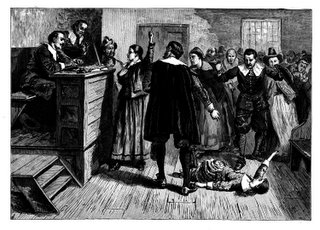

In brief, to name just three: Torture was gleefully perpetuated, as in the case of the witch hunts. There was the systematic persecution and slaughter of Native Americans. Most horrible of all, the institution of slavery was built, expanded and abetted with the cooperation of Christian churches of all denominations.

Were most Americans of the Civil War period Christians? Yes, they were.

Did any more than a tiny number of them, both north and south, really believe that African-Americans were human beings with souls?

No, they didn’t.

The Christian precepts of abolitionism in the sense of human slavery differed little from those that might have been cited concurrently as justification for abolishing cruelty to draft animals.

Exactly what part of this example of the “faith of our fathers” and our “Christian heritage” is relevant to conditions in our day and age – for that matter, to any day and age?

Predictably, Rep. Sodrel neither touches upon these abominations, nor does he consider their implications in the realm of faith, although he does manage to pay brief lip service to the concept of tolerance:

“In this age of tolerance, one would think the minority could show some tolerance for the majority.”

Such is Rep. Sodrel’s viewpoint from the luxury box seats at his exurban mega-church, and he expands on these sentiments with this, the congressman’s one true gem of misplaced rhetoric:

“No one is asking the minority to approve of, promote, or practice the majority faith. We only ask them to put up with us.”

To put up with you?

Speaking only for myself, this is something I’m quite willing to do, at least so long as the “majority faith” is not selectively defined as the evangelistic dogma of a valued and targeted segment of the electorate, and it is not cynically deployed as an excuse to rewrite the rules that apply to all of us in such a manner as to make such a specific religious interpretation into the law of the land – a land that I, a card-carrying member of the non-religious minority, inhabit with a certainty borne of Constitutional fact that Constitutional rights were meant to apply to me and mine as well as to Rep. Sodrel and his partisan voting bloc.

Have “fact and faith … coexisted in America for over 230 years,” as Rep. Sodrel writes?

Uneasily at best, and the proposition itself is debatable, but in their arguments thus far, both the congressman and the newspaper editor have freely sacrificed the facts to bolster the faith.

Why?

No comments:

Post a Comment